![]()

Children of Shoah Survivors

New Perspectives for Treatment and Research

Relevance of an ethnopsychiatric approach to the second generation

* Paper presented at Conference Seminar on Working with Holocaust Survivors

and their Families. World Council of Jewish Communal Service .

Jérusalem, Israël, November 11-13 1998

Relevance of an ethnopsychiatric approach to the second generation

* Paper presented at Conference Seminar on Working with Holocaust Survivors and their Families.

World Council of Jewish Communal Service . Jérusalem, Israël, November 11-13 1998

Since 1991, I have created rap groups for children of Shoah survivors in the Department of Psychology of the University of Paris 8 at Saint-Denis, France. These groups are research groups which meet for eight three-hour sessions, on sundays afternoons, over the course of an academic year. Each group includes seven or eight participants, all of whom are interviewed individually beforehand. There is no selection: all applicants are accepted. The groups are facilitated by two psychologists, researchers at the Georges Devereux Center, a university center of Ethnopsychiatry providing psychological assistance to immigrant families. In order to collect reliable data for research purposes, the sessions are videotaped. At the end of the year, a one-hour cut made from the videotapes is shown to the participants. We currently have 168 hours of videotapes, covering all 7 groups, and over 400 hours of audiotaped research interviews. Finally, participation to the group is free of charge [1].

![]() What is the

University Center of Ethnopsychiatry?

What is the

University Center of Ethnopsychiatry?

The Georges Devereux Center is a clinical research center founded by Professor Tobie NATHAN, hosted by the Psychology Department of the University of Paris 8. Its primary purpose is to study therapeutic techniques of every kind, "with none debarred or hierarchized" [2]. We study all forms of contemporary therapy, from hospital psychiatry to charismatic churches and "New Age" techniques, as well as the practices of traditional healers.In order to do this, a staff of approximately 40 multiethnic and multilingual reseachers (psychologists, ethnologists, linguists, psychiatrists)1) sees and treats patients within a university setting,2) carries out field work with therapists worldwide,3) analyzes and confronts data in research seminars4) give regular reports of their work in publications and conferences, both in France and abroad [3]..We strive to comprehend the functioning of practices, objects and theories used by therapists as well as their training (their initiation). The goal is to make intelligible the internal logic of these systems and to report in a rational way on their effectiveness.

![]() Why

an ethnopsychiatric group for children of Holocaust survivors ?Since

the 70's, the psychology and psychopathology of children of survivors

has generated an abundant literature. What conclusions were arrived

at? It was never possible to show that children of survivors were more

prone to neurosis or schizophrenia, or any other given pathology. In

fact, attempts at theorizing the psychology of this population have

given rise to an infinite number of propositions, usually psychoanalytically

based, which account for the theoretical models of the authors rather

than the specificity of the people in question[4].

This isn't surprising given that we are faced with a fundamental methodological

error, a remakable contradiction: when psychiatry, psychoanalysis and

psychology take interest in children of Holocaust survivors, they implicitly

assume the existence of a culturally determined category (Jews), and

yet they lack concepts, notions, or technical methods designed to apprehend

ethnic specificity. On the contrary, psychiatry and psychoanalysis –

like medicine – base their theories and practices on the notion

of universality . Hence, the Jewish dimension of children of Shoah survivors

has been clinically and theoretically totally obliterated, which, you'll

agree, is quite shocking, given that this ethnic specificity is fully

present in the very definition of the population the professionals wish

to study – not to mention the fact that the very identity of the

psychologists and psychiatrists specialized in the treatment of children

of survivors are almost all Ashkenazi Jews!In the context of our research,

we have to this day conducted in-depth psycho-historical interviews[5]

with over 150 survivors and children of survivors. 50 children of survivors

have taken part in the rap groups. Among these 50, 10 dropped out in

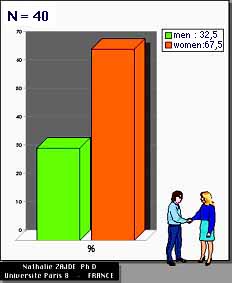

the course of the year and 40 completed the entire group.Statistics

pertaining to the 40 children of survivors who took part in the groups

computed before participation in the rap group.

Why

an ethnopsychiatric group for children of Holocaust survivors ?Since

the 70's, the psychology and psychopathology of children of survivors

has generated an abundant literature. What conclusions were arrived

at? It was never possible to show that children of survivors were more

prone to neurosis or schizophrenia, or any other given pathology. In

fact, attempts at theorizing the psychology of this population have

given rise to an infinite number of propositions, usually psychoanalytically

based, which account for the theoretical models of the authors rather

than the specificity of the people in question[4].

This isn't surprising given that we are faced with a fundamental methodological

error, a remakable contradiction: when psychiatry, psychoanalysis and

psychology take interest in children of Holocaust survivors, they implicitly

assume the existence of a culturally determined category (Jews), and

yet they lack concepts, notions, or technical methods designed to apprehend

ethnic specificity. On the contrary, psychiatry and psychoanalysis –

like medicine – base their theories and practices on the notion

of universality . Hence, the Jewish dimension of children of Shoah survivors

has been clinically and theoretically totally obliterated, which, you'll

agree, is quite shocking, given that this ethnic specificity is fully

present in the very definition of the population the professionals wish

to study – not to mention the fact that the very identity of the

psychologists and psychiatrists specialized in the treatment of children

of survivors are almost all Ashkenazi Jews!In the context of our research,

we have to this day conducted in-depth psycho-historical interviews[5]

with over 150 survivors and children of survivors. 50 children of survivors

have taken part in the rap groups. Among these 50, 10 dropped out in

the course of the year and 40 completed the entire group.Statistics

pertaining to the 40 children of survivors who took part in the groups

computed before participation in the rap group.

N=40: Female= 67,5% ; Male= 32,5%

![]() Symptoms

Symptoms

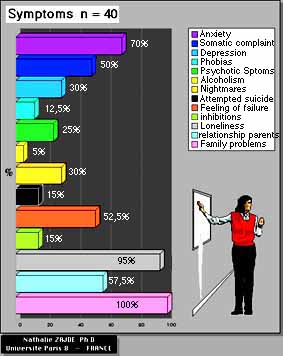

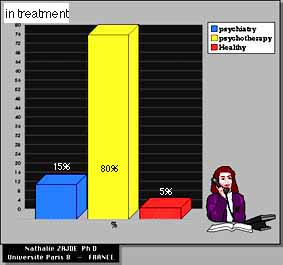

Anxiety= 70%; Somatic complaints, discontent= 50%; Depression= 30%; Phobias (agoraphobia, claustrophobia, social phobia, zoophobia etc.)= 12,5%; Psychosis= 25%; Alcoholism= 5%; Nightmares= 30%; Attempted suicide=15%; Feelings of failure= 52,5%; Inhibitions= 15%; Feelings of profound loneliness and of being misunderstood= 95%; Poor relationship with parents= 57,5%; Family problems= 100%

Psychiatric treatment= 15%; Psychotherapy= 80% ; 5% are healthy (they come to the group out of interest for the research topic but have no complaints).

![]() Ethnopsychiatric profile:

Ethnopsychiatric profile:

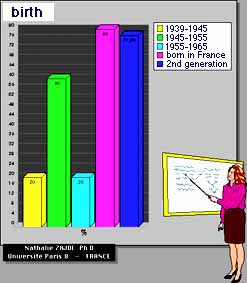

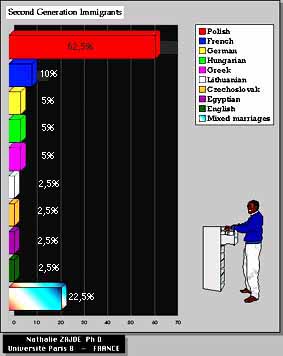

Birth

Born between 1936 and 1945= 20%; Born between 1946 and 1956=

60%; Born between 1957 and 1968= 20%; 80% born in France, the others

in Europe and 2 born in Israel; Second generation immigrants= 77,5%

Parents: Polish Jews= 62,5%; Greek Jews= 5%; French Jews=

10%; Hungarian Jews= 5%; Lithuanian Jews= 2,5%; Czechoslovak Jews=%;

German Jews= 5%; British Jews= 2,5%; Egyptian Jews= 2,5%; Chilren of

mixed marriages with Christians= 22,5%.

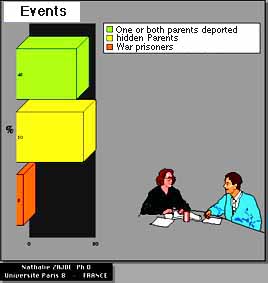

One or both parents deported to concentration camps= 45%;

Hidden parents= 55%; and 5% had fathers who were deported as war prisoners.

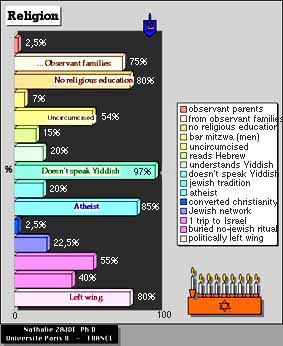

Observant parents (shomer shabbat)= 2,5%; From observant families two generations ago (grand parents)= 75%; Having received no religious education= 80%; Bar mitsvah: 7% of the men; Uncircumcised=54% of the men; Able to read Hebrew (most often recently learned)=15%; Understands Yiddish= 20%; Doesn't speak Yiddish= 85,5%; Somewhat follows Jewish tradition (In France, this means knowing the dates of holidays, and doing something to mark the occasion, given that our calendar is Christian)= 20%; Claims to be an atheist= 85%; Converted to Christianity= 2,5%; Involved in a Jewish network (charity organization, synagogue, cultural organization, etc.)= 22,5%; Having been to Israel at least once= 55%; Buried deceased parent(s) without performing any Jewish ritual or saying Kaddish (out of the 20 with at least one dead parent)= 40%; Politically Left wing= 80%.

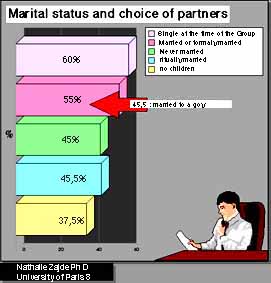

Single (at the time of the group)= 60%; Married or formerly married

to a goy= 45,5%; Never married= 45%; Ritually married (ketubah)= 45,5%;

No children= 37,5%.

![]() Comments

Comments

The ethnopsychiatric pictures clearly show that we explore a different set of elements. In order to apprehend the rap group participants, we refer to a series of facts and preoccupations having to do with a much wider perspective and more importantly which concern people as individuals as well as the sociocultural groups they belong to.

![]() Rap group content and processes

Rap group content and processes

In the groups, past or present experiences and thoughts are shared, confronted, compared. We talk about intimate aspects of ourselves, and we realize that what we thought was the most hidden, the most secret, the most idiosyncratic, is in fact shared by others. Time and again, we discover that the most intimate part of children of survivors turns out to be the most common!

For example a female participant says:

– "How did my mother manage to have a child when she came out of Auschwitz? At 35, I haven't even been able to find a husband, much less have a child!"

Another answers:

– "I know what you mean, but I don't want children. I'd be too afraid of passing on the neurosis my parents passed down to me!"

Or,

–"My father can read Yiddish and I can't even speak it! We've lost so much!"

A man answers:

–"Now that he's dead, I feel compelled to go find the information I'm missing. I need to find things out so that I can pass them on to my children. But it's hard to have to do that on your own."

Or,

–"Our parents suffered so much, how come they make us suffer? And when they're so hard on us like that, how can you deal with them without adding to their suffering? My parents sometimes make me so angry, I get sick from holding back!"

A woman answers:

–"My therapist tells me I should stop seeing my parents, to distance from them. Maybe he's right, but how could I do that? They're going to die soon, and then what will I be left with?"

Or,

–"I can't stand living as a couple, I'm too anxious. And as soon as a woman gets too close to me, I feel as if I'm suffocating. Maybe because my mother overprotected me when I was little, because of the fears she lived through during the war."

–"Yes, I also experienced that overprotection and the constant worry of my parents. It was stifling!"

While sharing freely and spontaneously these experiences both varied and similar, we discuss different theories, different matrixes of interpretation:

What interpretation does Psychiatry offer? What solution? What diagnoses were arrived at: Psychosis? Neurosis? Depression? What etiologies: biological? Genetic? Reactional? What treatment: psychotherapy? Medication? (Anxiolytics, neuroleptics, antidepressants, etc) What matrix of explanation do our therapists (psychoanalysts, family therapists, etc) offer? Failure of separation-individuation mechanisms, Oedipal complex, trauma, etc... What therapeutic solutions: catharsis, transference analysis, sublimation, uncovering of fantasies, etc.

I must say that participants are quite familiar with these notions given that they often have had a long experience of therapy. In other words, they have literally been "initiated" by their therapy.

Within the same rationale of exploring and discussing different systems of meaning, we also mention what Jewish therapists might offer, what interpretations, theories and especially therapeutic solutions the Jewish matrix can provide. This perspective is much less known to the participants considering their sociocultural, intellectual, and especially therapeutic histories.

![]() A brief example of a Jewish interpretation pertaining to relationship

problems between parents and children in survivor families

A brief example of a Jewish interpretation pertaining to relationship

problems between parents and children in survivor families

A facilitator: "Traditionally, survivors are said to have a special status: they belong to the just, tsaddikim. If we constantly come up against them, it's because we don't understand that they're different, they're "initiated", their nature is different from that of ordinary humans, because of their extraordinary experience. We need to identify their nature in order to connect with them without clashing with them."

A participant: "It's true that they're different from others. Sometimes it even seems as though they're not human."

A facilitator: "They're the first of a new lineage, they're apart. Like the founding fathers in the Torah who, as such, are different from preceding or following generations."

We continued to explore participants' specific experience of the Shoah, the analogy with extraordinary experiences known in Jewish mythology, identifying and understanding the specific nature of the Tsaddik, the discussion of Jewish understanding of such people and its logic, as well as ways of establishing appropriate relations with them, as prescribed by ancestral tradition.

What do these exchanges produce? A redefining of self.

This kind of interpretation triggers among participants new definitions of self. On their own – either through readings, or actions, or new commitments – they change the way they perceive themselves. Participation in these rap groups generates notable change among most group members – either during the year of the group, or one, two, sometimes three years later. We've noted weddings, the birth of children, the decision by a member's psychiatrist to end the prescription of psychoactive drugs, the disappearance of depressive states, the resolution of inhibitions and death fears, etc. I must point out that initial intellectual postitions remain unchanged: the leftists remain leftists, the atheists stay atheists, etc... Perhaps the pro-Palestinians and antisionists are a little less so... There isn't enough time for me to detail specific changes for each participant, but what is general and shared by all is the durable disappearance of the feeling of isolation and profound loneliness unanimously complained of at the beginning accompanied by a significant autonomy with regard to the rap group as a psychological setting [6].

![]() Logical implications of the recourse to the Jewish matrix of interpretation

Logical implications of the recourse to the Jewish matrix of interpretation

1) it offers meaning which is relevant for all the members of the group

2) it also offers meaning for the families of group members to which they can thus connect – instead of isolating them even more, separating them from their parents, from their surviving ashkenazi families, from their source, as psychoanalysis and psychiatry inevitably do since they affiliate them to non Jewish systems of interpretation of misfortune and discomfort, to "foreign" philosophical and existential systems[7].

In other words, the reference to and explanation of the Jewish matrix of meaning, allow children of survivors to become reaffiliated to their parents and extended families, by offering ways of understanding problems that include group participants, surviving parents, dead parents, children and future generations.

![]() To conclude

To conclude

The ethnopsychiatric approach is a new approach which makes it possible to take into consideration all the different perspectives and networks pertaining to children of survivors of the Shoah. It also offers the possibility to consider within its setting the Jewish aspect of our population, thus affording children of survivors access to a sociocultural and therapeutic network capable of embracing all facets of their personality.

![]() Final question

Final question

Why might clinical psychologists be interested in Jewish therapeutic practices? 1) because it is an ancestral reality of the field which is presently undergoing a spectacular revival in Europe as well as in America and Israel[8] 2) because the Jewish population is tending towards a greater and greater use of these therapeutic ressources 3) because we wish to understand and explicit their effectiveness 4) finally, because tending to this kind of reality can help us expand the limits of our own field, to question it and thereby enrich it.

write to the author : Nathalie Zajde

![]() Bibliography:

Bibliography:

NATHAN T. - 1999: Georges Devereux and Clinical Ethnopsychiatry. in Dany Nobus (Editor), Freudian Currencies: Essays on the Cultural Limits of Psychoanalysis, London-New York NY, Routledge, 1999.

NATHAN T. - 1998: Eléments de psychothérapie in Psychothérapies, Paris Ed. Odile Jacob.

NATHAN T. - 1997: Spécificité de l'ethnopsychiatrie, Nouvelle Revue d'Ethnopsychiatrie, 34, pp. 7-24. Ed. La pensée sauvage, Grenoble.

NATHAN T. - 1995: Manifeste pour une psychopathologie scientifique. in Tobie Nathan et Isabelle Stengers, Médecins et sorciers, Paris, Ed. Les empêcheurs de penser en rond.

NATHAN T. -1994: L'influence qui guérit. (Une théorie générale de l'influence thérapeutique) Paris, Odile Jacob.

NATHAN T. -1993: Fier de n'avoir ni pays ni amis, quelle sottise c'était… Principes d'ethnopsychanalyse. Editions de la Pensée Sauvage, Grenoble, 180 p.

WEXLER H., DAVID P. NATHAN T. - 1996: "Tohu wa bohu. Réflexions ethnopsychiatriques sur la technique d'un guérisseur yéménite en Israël"."Nouvelle Revue d'Ethnopsychiatrie, 31. pp. 13-34

ZAJDE N. - 1993: Enfants de survivants, réédition :1995, Paris, éditions O. Jacob.

ZAJDE N. et GRANDSARD C. - 1996: "Kaddish. Rituel de deuil dans un groupe de parole d'enfants de survivants de la Shoah."Nouvelle Revue d'Ethnopsychiatrie, 31. pp. 119-138

ZAJDE N. - 1996: "La névrose ou la poule? Note ethnopsychanalytique sur le "petit homme-coq", les poulets de Kappara et la circoncision", Nouvelle Revue d'Ethnopsychiatrie, 31. pp. 35-52.

ZAJDE N - 1995: "Un mort non disloqué. Analyse ethnopsychiatrique des processus de deuil chez la fille d'un disparu en camp d'extermination". in Nathan et Coll. Rituels de deuil, travail de deuil, ed. La Pensée sauvage, Grenoble. pp.103-126.

Notes

[1]. For a detailed description of the clinical research setting, see Zajde 1993, 1995, Zajde & Grandsard, 1996.

[2]. See Nathan, 1997, 1999.

[3]. For a full presentation and explanation of the Georges Devereux Center, see Nathan 1993, 1994 and 1995.

[4]. For a review of the literature, see Zajde, 1995.

[5]. See Zajde N. op.cit.

[6]. Hence, such a clinical setting, though brief and free of charge, generates significant and durable change processes among participants while producing no effect of relational dependency in the form of attachement to the clinicians or to the setting. These are points of interest in as much as they introduce new questions among the commonly accepted ideas regarding the nature of relationships in treatment settings (transference).

[7]. For a discussion of therapeutic approaches as affilation systems, see Nathan, 1998 and Nathan, 1995.

[8]. See Wexler, David & Nathan, 1996 and Zajde, 1996.

Nathalie Zajde and Catherine Grandsard